Books suspended from the ceiling of the Café Tettamanzi, Nuoro, Sardinia

This December marks the ninth year of seraillon, which has admittedly been limping along a bit these past few years. My reading, though, has continued almost apace and with some tremendous discoveries this year, so I’ll share more than just a few highlights from works I read in 2019, particularly given how few of them I’ve actually written about to date. Perhaps you might consider this like one of those summary annual holiday letters from a remote relative that superficially fills you in on the past year’s goings-on among people you may or may not know.

Instead of the usual year end “best of” list, I’m making two lists. Beginning with my reading of Ludovico Ariosto’s Orlando furioso midway through 2014 - so for approximately half of the blog’s existence - I’ve turned a good part of my reading attention to Italian literature in translation. Today’s post will feature Italian literature highlights. A second post, to follow, will feature highlights from everywhere else.

Borgo Vecchio, Giosuè Calaciura (French translation; currently unavailable in English)

Lise Chapuis, translator, Notabilia

The inhabitants of Borgo Vecchio, a quarter in an unnamed coastal Italian city, live the same entrenched poverty, entrapment and urban violence one can find in Pasolini’s novels of street life in Rome or the Neapolitan works of Elena Ferrante. But Calaciura’s cruel world is also saturated in ineffable beauty. If there’s one contemporary work, Italian or otherwise, that sent me over the moon this past year, it’s this one. Calaciura’s short novel burns like ignited magnesium, an operatic opus of violence and tenderness that glitters with flashes of wings and knives to illuminate this forgotten quarter, where bitter realities gust into magic and lift the Borgo Vecchio off its weary feet for instants now and then. Told with minimal dialogue – there are probably fewer than a dozen spoken lines in the entire work – Borgo Vecchio is a fugue of poetry wrapped around resolution of a simple and terrible problem articulated in the first chapter: the savage nightly beatings suffered by poor young Cristofaro at the brute hands of his drunken father. The matter runs from the beginning of the novel to the end like a taut clothesline on which Calaciura hangs his phantasmagoric portrait of Borgo Vecchio. His cast of characters is small: Cristoforo and his best friend Mimmo; Celeste, their female friend and daughter of the religiously devout prostitute Carmela; and the pistol-packing thief Toto, whom all of the children wish to be their father and who himself wishes to marry Carmela. And then there are the nameless or scarcely-named people of the quarter who serve as a kind of Greek chorus, recoiling behind closed doors and shutters at Cristoforo’s nightly “howl like that of a sick dog,” raining bottles and stones down on the cops whenever there’s a raid, going about their daily business with little hope or expectation of change. Calaciura works his tale into a kind of generalized fable into which any such neighborhood in any such city might fit, and which borrows from a long fabulist tradition in Italian literature. Beneath the dust jacket of the beautifully designed French edition from Notabilia one finds the image of a broken Pinocchio, which gives one some idea of Calaciura’s world, one not so different, really, from that of Carlo Collodi. The author has yet to be translated into English; I expect to hear a great deal more about him when he is.

The inhabitants of Borgo Vecchio, a quarter in an unnamed coastal Italian city, live the same entrenched poverty, entrapment and urban violence one can find in Pasolini’s novels of street life in Rome or the Neapolitan works of Elena Ferrante. But Calaciura’s cruel world is also saturated in ineffable beauty. If there’s one contemporary work, Italian or otherwise, that sent me over the moon this past year, it’s this one. Calaciura’s short novel burns like ignited magnesium, an operatic opus of violence and tenderness that glitters with flashes of wings and knives to illuminate this forgotten quarter, where bitter realities gust into magic and lift the Borgo Vecchio off its weary feet for instants now and then. Told with minimal dialogue – there are probably fewer than a dozen spoken lines in the entire work – Borgo Vecchio is a fugue of poetry wrapped around resolution of a simple and terrible problem articulated in the first chapter: the savage nightly beatings suffered by poor young Cristofaro at the brute hands of his drunken father. The matter runs from the beginning of the novel to the end like a taut clothesline on which Calaciura hangs his phantasmagoric portrait of Borgo Vecchio. His cast of characters is small: Cristoforo and his best friend Mimmo; Celeste, their female friend and daughter of the religiously devout prostitute Carmela; and the pistol-packing thief Toto, whom all of the children wish to be their father and who himself wishes to marry Carmela. And then there are the nameless or scarcely-named people of the quarter who serve as a kind of Greek chorus, recoiling behind closed doors and shutters at Cristoforo’s nightly “howl like that of a sick dog,” raining bottles and stones down on the cops whenever there’s a raid, going about their daily business with little hope or expectation of change. Calaciura works his tale into a kind of generalized fable into which any such neighborhood in any such city might fit, and which borrows from a long fabulist tradition in Italian literature. Beneath the dust jacket of the beautifully designed French edition from Notabilia one finds the image of a broken Pinocchio, which gives one some idea of Calaciura’s world, one not so different, really, from that of Carlo Collodi. The author has yet to be translated into English; I expect to hear a great deal more about him when he is.

The Day of Judgment, Salvatore Satta

Patrick Creagh, translator, Apollo

Satta’s The Day of Judgment stood out among an already outstanding selection of novels from Sardinia I read this year. It’s also one of the finest 20thcentury novels I’ve read in any year. An autobiographically-based work, The Day of Judgment paints a profound portrait of the author’s hometown of Nuoro in the inland Barbagia region of Sardinia. Recounted in a stoically ironic tone combining bitterness, humor and an almost irrepressible compassion, Satta’s novel limns his fellow citizens in this place where one is “only in this world because there’s room for you,” and where the inhabitants go about their lives in a kind of torpor, more dead than alive, their actions accruing to little more than “the usual story.” But The Day of Judgment is anything but the usual story; the title refers to the biblical day of judgment, here a kind of tallying up of the town’s lives (and lifelessness) - as well as of the life of the narrator himself. Satta’s novel is a stunning portrait not only of his hometown, but also of an intellectual estranged from family and community and held fast by his origins. The renowned jurist’s only work of fiction, on which he worked in secret for 30 years, is also memorable for its depiction of a vanishing way of life, comparable to Giuseppe di Lampedusa’s The Leopard.

Satta’s The Day of Judgment stood out among an already outstanding selection of novels from Sardinia I read this year. It’s also one of the finest 20thcentury novels I’ve read in any year. An autobiographically-based work, The Day of Judgment paints a profound portrait of the author’s hometown of Nuoro in the inland Barbagia region of Sardinia. Recounted in a stoically ironic tone combining bitterness, humor and an almost irrepressible compassion, Satta’s novel limns his fellow citizens in this place where one is “only in this world because there’s room for you,” and where the inhabitants go about their lives in a kind of torpor, more dead than alive, their actions accruing to little more than “the usual story.” But The Day of Judgment is anything but the usual story; the title refers to the biblical day of judgment, here a kind of tallying up of the town’s lives (and lifelessness) - as well as of the life of the narrator himself. Satta’s novel is a stunning portrait not only of his hometown, but also of an intellectual estranged from family and community and held fast by his origins. The renowned jurist’s only work of fiction, on which he worked in secret for 30 years, is also memorable for its depiction of a vanishing way of life, comparable to Giuseppe di Lampedusa’s The Leopard.

L’île, Giani Stuparich (in French; currently unavailable in English)

Gilbert Bosetti, translator, Éditions Verdier

I’ve already written about Giani Stuparich’s short novella L’Île here. In this gem of concision, the restrained text seems an island itself within a vast sea of psychological affect surrounding the novel’s subject: the difficulty of speaking, of finding the words to say it, “it” in this case being the impending death of a father, ill with esophageal cancer, on a final visit to the island of his youth in the company of his estranged son. An unforgettable, deeply moving book, one I returned to repeatedly throughout the year.

I’ve already written about Giani Stuparich’s short novella L’Île here. In this gem of concision, the restrained text seems an island itself within a vast sea of psychological affect surrounding the novel’s subject: the difficulty of speaking, of finding the words to say it, “it” in this case being the impending death of a father, ill with esophageal cancer, on a final visit to the island of his youth in the company of his estranged son. An unforgettable, deeply moving book, one I returned to repeatedly throughout the year.

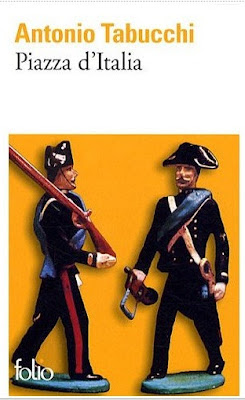

Et enfin septembre vint, Antonio Tabucchi (in French; currently unavailable in English)

Martin Rueff, translator, Éditions Chandeigne

It would hardly seem credible to have on a “best of” list like this a 20-page fragment of an unfinished work. Such a book, even from an author I admire so much as Tabucchi, might seem but a publisher’s completist effort to capitalize on whatever scraps the writer might have left behind. Au contraire. Tabucchi’s little book, four rough chapters of a planned novel dating from 2011, succeeds in giving enough shape to the anticipated finished product that I found myself despairing that he’d been unable to complete it. Tabucchi bases his narrative on a visit he made in the waning years of the Salazar dictatorship to a remote Portuguese village in the company of a group of linguists determined to preserve and document a dying language. Their arrival coincides, however, with that of news of a native son’s death in one of Portugal's colonial wars in Africa, which unleashes the village’s collective grieving centered around the young soldier’s bereft mother. Despite its brevity, Tabucchi’s sketch is of a remarkable complexity, exploring the destruction of and pernicious effects of fascism on language. I read the book while in Sardinia, just prior to a visit to Antonio Gramsci’s home, and was surprised to find Tabucchi turning away from his typical engagement with Fernando Pessoa and towards Gramsci, in particular his theories on language and literature. The edition itself, from Éditions Chandeigne, is a lovely book containing the original Italian with Martin Rueff's French translation on facing pages, and a Portuguese translation by Tabucchi’s widow, Maria José de Lancastre.

It would hardly seem credible to have on a “best of” list like this a 20-page fragment of an unfinished work. Such a book, even from an author I admire so much as Tabucchi, might seem but a publisher’s completist effort to capitalize on whatever scraps the writer might have left behind. Au contraire. Tabucchi’s little book, four rough chapters of a planned novel dating from 2011, succeeds in giving enough shape to the anticipated finished product that I found myself despairing that he’d been unable to complete it. Tabucchi bases his narrative on a visit he made in the waning years of the Salazar dictatorship to a remote Portuguese village in the company of a group of linguists determined to preserve and document a dying language. Their arrival coincides, however, with that of news of a native son’s death in one of Portugal's colonial wars in Africa, which unleashes the village’s collective grieving centered around the young soldier’s bereft mother. Despite its brevity, Tabucchi’s sketch is of a remarkable complexity, exploring the destruction of and pernicious effects of fascism on language. I read the book while in Sardinia, just prior to a visit to Antonio Gramsci’s home, and was surprised to find Tabucchi turning away from his typical engagement with Fernando Pessoa and towards Gramsci, in particular his theories on language and literature. The edition itself, from Éditions Chandeigne, is a lovely book containing the original Italian with Martin Rueff's French translation on facing pages, and a Portuguese translation by Tabucchi’s widow, Maria José de Lancastre.

Birth and Death of the Housewife, Paola Masino

Marella Feltrin-Morris, translator, SUNY Press

Marella Feltrin-Morris, translator, SUNY Press

Massimo Bontempelli, the modern inventor of “realismo magico,” one of the 20thcentury’s most recognized literary genres, made my 2018 “best of” list. I’d been unaware that his spouse, Paola Masino, had been an author of perhaps even greater daring (at age 16, Masino had approached Luigi Pirandello to ask him to produce a play she had written). Masino’s originality is in full display in her best-known work, Birth and Death of the Housewife (Nascita e morte della massaïa, 1945, first published in installments in 1941-42). This dense, lyrical, disturbing, stylistically inventive, even lacerating novel employs the narrative advertised by its title to engage in a borderline surrealistic dissection of the Fascist ideals of womanhood and the centrality of family. The novel opens with the housewife as a child, living inside of a trunk filled with books, bits of bread, spider webs and moss, desperately consumed with the idea that she is doomed to kill her own mother with heartbreak. The housewife emerges from her trunk, is presented to the world at a coming-out party, meets a dark-haired suitor who kisses her and disappears, then marries a distant cousin who plops her into a “wretched” life of idleness and management of servants. Linearity then takes a detour, as the housewife voyages through often nightmarish scenes of domesticity via diary entries, dreams, letters, a dramatic play set within the novel, all the while shifting between acquiescence and rebellion, a journey through a twilit landscape which at times resembles the paintings of Giorgio de Chirico, Masino’s colleague and friend, or the lugubrious, stark atmosphere of Jane Bowles’ Two Serious Ladies. Masino’s protagonist is a stunningly compelling character - disquieting, uncontainable, ferocious and sympathetic at once. “This story has no room for general ideas,” states the housewife. The particulars, one must admit, are quite enough. The novel is not easy to find, but well worth the trouble.

The Periodic Table, Primo Levi

Raymond Rosenthal, translator, Everyman's Library

I read this in conjunction with a blogging event proposed at Dorian Stuber’s Eiger, Mōnch & Jungfrau blog to mark the centennial of Levi’s birth, but I never got around to posting anything (sorry Dorian!). While Levi’s If This is a Man (Survival in Auschwitz in the American version) is required reading for most Western European schoolchildren, those who fail to explore Levi’s other works will have a skewed impression of this giant of world literature, who here uses a series of pieces each named after an element of Mendeleev’s periodic table as launching pads for…what exactly? Written in an almost indefinable genre - part autobiography, part collection of essays, part novel, part philosophy, all intelligence and probing - The Periodic Table ought to be added to those required reading lists. Levi uses his training as a chemist to explore notions of matter and spirit, purity and impurity, difference and similarity, affinity and repulsion, reaction and stasis – forces present in all human relations, “and not only the chemist’s trade.” The book’s 21 chapters weave autobiography with observations on science and on the rise of Fascism, culminating in an ending like something Italo Calvino might have written. Could there be any greater modern example of the persistent legacy of the Italian Renaissance, of the blending of science, art and humanism as means for seeking both truth and humanity? I also reread Levi’s The Search for Roots, a book of literary excerpts that helped form Levi’s world view, and which has provided a path, directly or indirectly, to more than a few other works I read this year.

I read this in conjunction with a blogging event proposed at Dorian Stuber’s Eiger, Mōnch & Jungfrau blog to mark the centennial of Levi’s birth, but I never got around to posting anything (sorry Dorian!). While Levi’s If This is a Man (Survival in Auschwitz in the American version) is required reading for most Western European schoolchildren, those who fail to explore Levi’s other works will have a skewed impression of this giant of world literature, who here uses a series of pieces each named after an element of Mendeleev’s periodic table as launching pads for…what exactly? Written in an almost indefinable genre - part autobiography, part collection of essays, part novel, part philosophy, all intelligence and probing - The Periodic Table ought to be added to those required reading lists. Levi uses his training as a chemist to explore notions of matter and spirit, purity and impurity, difference and similarity, affinity and repulsion, reaction and stasis – forces present in all human relations, “and not only the chemist’s trade.” The book’s 21 chapters weave autobiography with observations on science and on the rise of Fascism, culminating in an ending like something Italo Calvino might have written. Could there be any greater modern example of the persistent legacy of the Italian Renaissance, of the blending of science, art and humanism as means for seeking both truth and humanity? I also reread Levi’s The Search for Roots, a book of literary excerpts that helped form Levi’s world view, and which has provided a path, directly or indirectly, to more than a few other works I read this year.

Partisan Diary: A Woman’s Life in the Italian Resistance, Ada Gobetti

Jomarie Alano, translator, Oxford University Press

A few names mentioned in Levi’s The Periodic Table seemed awfully familiar to me when I read anti-Fascist Ada Gobetti’s Partisan Diary: A Woman’s Life in the Italian Resistance. The title delivers precisely what it promises: an almost daily account of the work of the woman at the heart of the resistance effort in Italy’s north where the Gobetti and Levi, both Torinese, knew many of the same people. A woman of extraordinary political and tactical acumen, Gobetti allowed her home to become ground zero for the movement. Despite an utterly frenetic level of activity devoted to publishing leaflets, organizing operations, rescuing partisans trapped behind enemy lines, ensuring safe houses and keeping up a steady and determined self-education in politics, Gobetti managed to pass herself off as an ordinary housewife. At the sentence level, the writing of Partisan Diary can at times seem pedestrian; but small matter - the suspense Gobetti brings to each ordinary day under such perilous conditions made this a book I felt compelled to rush home and read each evening.

A few names mentioned in Levi’s The Periodic Table seemed awfully familiar to me when I read anti-Fascist Ada Gobetti’s Partisan Diary: A Woman’s Life in the Italian Resistance. The title delivers precisely what it promises: an almost daily account of the work of the woman at the heart of the resistance effort in Italy’s north where the Gobetti and Levi, both Torinese, knew many of the same people. A woman of extraordinary political and tactical acumen, Gobetti allowed her home to become ground zero for the movement. Despite an utterly frenetic level of activity devoted to publishing leaflets, organizing operations, rescuing partisans trapped behind enemy lines, ensuring safe houses and keeping up a steady and determined self-education in politics, Gobetti managed to pass herself off as an ordinary housewife. At the sentence level, the writing of Partisan Diary can at times seem pedestrian; but small matter - the suspense Gobetti brings to each ordinary day under such perilous conditions made this a book I felt compelled to rush home and read each evening.

The Sergeant in the Snow, Mario Rigoni Stern

Archibald Colquhoun, translator, Marlboro Press

Among many pieces of writing included in Primo Levi’s The Search for Roots, a short but riveting excerpt from Mario Rigoni Stern’s novel, The Story of Tonle, prompted me a few years ago to read the whole book, a terrific fictionalized account of war in the Tyrol. An Italian bookstore owner this year recommended The Sergeant in the Snow as the last novel she’d read that had left her in tears, so I took her up on what I'm pretty sure she meant as a recommendation. Stern’s novel belongs with the best of fiction about WWII. Specifically, it recounts the harrowing retreat of the AIRAM (the Italian Army in Russia) from positions along the Don River near Stalingrad in the terrible winter of 1943-44. This is about as raw as war fiction comes, which is not to say that it’s all blood and gore. Rather, for some 150 pages, Stern conveys the relentless obligation of soldiers to keep placing one foot in front of the other, literally, in order to survive their 300 mile march through deep snow, carrying heavy equipment, under fire, in temperatures that dipped as low as -40 C. But Stern’s narrative offers a steady reckoning of the capriciousness of war against such resilience: that one can take precautions, do everything in order to live, and still lose one’s life in a split second – or find the most unexpected kindnesses. I also read Stern’s short non-fiction work Arbres en liberté. Translator Monique Baccelli claims the Italian title, Arboreto salvatico (1991), with its deliberate corruption of the second word into something suggesting “wood,” “wild” and “rescue,” might be approximated as “arboretum sauvage à sauver” – a wild arboretum to save. This is as lovely an appreciation of trees as one is likely to find in any language, consisting of short essays about individual tree species growing on Stern’s land, most of which he’d planted himself.

Among many pieces of writing included in Primo Levi’s The Search for Roots, a short but riveting excerpt from Mario Rigoni Stern’s novel, The Story of Tonle, prompted me a few years ago to read the whole book, a terrific fictionalized account of war in the Tyrol. An Italian bookstore owner this year recommended The Sergeant in the Snow as the last novel she’d read that had left her in tears, so I took her up on what I'm pretty sure she meant as a recommendation. Stern’s novel belongs with the best of fiction about WWII. Specifically, it recounts the harrowing retreat of the AIRAM (the Italian Army in Russia) from positions along the Don River near Stalingrad in the terrible winter of 1943-44. This is about as raw as war fiction comes, which is not to say that it’s all blood and gore. Rather, for some 150 pages, Stern conveys the relentless obligation of soldiers to keep placing one foot in front of the other, literally, in order to survive their 300 mile march through deep snow, carrying heavy equipment, under fire, in temperatures that dipped as low as -40 C. But Stern’s narrative offers a steady reckoning of the capriciousness of war against such resilience: that one can take precautions, do everything in order to live, and still lose one’s life in a split second – or find the most unexpected kindnesses. I also read Stern’s short non-fiction work Arbres en liberté. Translator Monique Baccelli claims the Italian title, Arboreto salvatico (1991), with its deliberate corruption of the second word into something suggesting “wood,” “wild” and “rescue,” might be approximated as “arboretum sauvage à sauver” – a wild arboretum to save. This is as lovely an appreciation of trees as one is likely to find in any language, consisting of short essays about individual tree species growing on Stern’s land, most of which he’d planted himself.

Bloodlines, Marcello Fois

Silvester Mazzarella, translator, MacLehose Press

Of the two novels I read this year by contemporary Nuorese author Marcello Fois, the powerful Bloodlines (Stirpe, 2009) impressed me most (which implies no disparagement of the other excellent work, The Advocate [Sempre Caro, 2004]). Bloodlines is not an easy book; borrowing from Dante’s Divine Comedy to portray the history of the Chironi family of Lollove, a small village on Nuoro’s outskirts, Fois holds back nothing in relating one terrible hardship after another extending across three generations. But no one would mistake this for pure realism; Fois is self-consciously literary, taking an approach which mixes elements of crime fiction with cultural ethnography while also engaging directly with his literary predecessors, particularly Salvatore Satta. In fact, in both novels, Fois references episodes in The Day of Judgment, a way of paying critical homage to his predecessor and, in building on a foundation already laid, pulling Sardinian literature into a new register while at the same time grounding his work in Sardinian particularities that convey a high-resolution picture of village life in the Barbagia.

Honorable mentions go to: Piero Chiara’s The Bishop’s Bedroom and The Disappearance of Signora Giulia, Michela Murgia’s Accabadora, Antonio Moresco’s A Distant Light and Ann Cornelisen’s Torregreca, about as deep into Italy as a non-Italian can go, a profound immersion into mid-20thcentury village life in Basilicata.