An impressive literature has grown up around Italy’s

partisans, those resistants who, particularly after the September 1943

ascension of Marshal Badoglio in Rome and the flight of Mussolini’s government

to the town of Salò in the north, took to the hills to fight against Germany’s

ferocious response to these events and against the Fascists who helped the

Nazis along. Warfare under these circumstances became largely a series of

attacks, raids and brutal reprisals against civilians, a civil war within the

larger conflagration engulfing Europe.

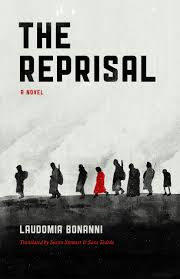

Laudomia Bonanni’s short novel The Reprisal (La

Rappresaglia) is as direct an approach to this subject as its title suggests.

Bonanni, who grew up in the mountainous Abuzzo region where she sets her novel,

goes for a particularly harrowing example of the types of reprisals that took place

during the winter of 1943-44. A woman carrying hidden arms is seized by a small

group of Fascist men and an adolescent boy hiding out in an abandoned monastery

near the end of the war; discovering that she is in the late stages of

pregnancy, they elect to delay her execution until she can deliver the child.

This is not a new literary topic, the examination of emotions

and moral questions transpiring between the condemned and their accusers, but

Bonanni’s choice of protagonist allows her to explore a range of issues around

female independence and assertiveness; male attitudes towards women, sexuality

and maternity; the complicity of the Catholic Church in the conflict; and above

all the struggle to find dignity and meaning in a world ripped apart by war

pitting neighbor against neighbor. In addition, The Reprisal is a rare

work that attempts, albeit over only a few of its 140 pages, to deal with the

suspicion-filled postwar co-existence of persons so recently committed to

killing one another. Bonanni also cleverly evokes an image of the Holy Family, sans

Joseph, the woman’s bare monastery cell echoing the simple manger where the

Christ child was born, a fixed point to which other visitors are drawn: the

monastery’s priest, a couple of wandering shepherds, two passing German

soldiers, and two of the Fascists’ wives, who arrive with supplies. These last,

complicit but at the same time aware enough to know that their husbands’

decision will haunt them the rest of their lives, serve to underscore Bonanni’s

themes of an endless cycle of reprisals, the participants inescapably linked

“by a chain,” and of the potential of women to break the cycle and chain.

Bonanni’s story makes for a close and intense reading

experience. Her characters stand out starkly, as though conceived for the

stage. Most memorable, certainly, is the woman herself, La Rossa, a paragon of

fierce defiance who, by driving a wedge directly between her male captives’

divergent views of women as sexual objects and as revered mothers, exposes

their weaknesses. Through caustic, pointed barbs and lengthy remonstrations, she

strips the men of their pretentions to morality and compassion, leaving their

violence and inadequacy raw and exposed. And yet Bonanni never allows La Rossa

to become a caricature; her own weaknesses and vulnerabilities are on full

display. When the oldest among her captives, Babaro, refuses to hand her over

to the Germans because of the deal they have all made to spare her child, La

Rossa responds with a searing mixture of contempt, sarcasm and palpable

desperation:

“The child, eh, they pass the buck.

Your good conscience is anxious for the innocent. You have captured me, kill me

then. Go ahead, hand me over to eh Germans. They do not make a fuss, those

people. They kill quickly. I want you to hurry up.” She was shouting now.

“C’mon, riddle me right away. You have to shoot here, make a sieve of this

whore’s belly with everything that’s inside it. Man’s semen, ha-ha. I’d like to

use my nails to tear out the fruit of your filthy race of male hypocrites.” She

was crumpling her skirt, panting as if her belly were fatally weighing her

down.

Bonanni reveals this male hypocrisy again and again, for

example through the Fascists’ risible attempt at a Christmas celebration and

the priest’s insistence on ritual and absolution while the sentence against the

woman hovers above all their futile attempts to live beyond the length of the

chain that binds them. As the birth approaches, one of the men, Annaloro,

anxiously exclaims, “We need boiling water. When my wife is giving birth, I am

always given the job of boiling water.”

“Just to get you out of the way,” La

Rossa teased, recovering in a moment of temporary relief. “Are you afraid I

might get an infection in the next world?”

The adolescent boy, himself a victim of the war, his legs

burned by a fire set by partisans, serves as foil and contrast to the older men

around him, poignantly and painfully taking on their worst excesses yet

retaining the emotional immaturity of a child. At once the most vicious and

vulnerable of the males in the story, he plays a critical role in developing

Bonanni’s themes regarding innocence and the responsibility of the world towards

children.

What distinguishes The Reprisal from many other

stories of partisan warfare is not only its focus on female experience, but

also its employment of a highly imaginative narrative strategy. First Bonanni

offers the conceit of a hidden story, proclaimed in the novel’s first lines:

“These facts have never been revealed. No one has ever breathed a word. Everything

buried. Soon the last shovelful of dirt will drop, so to speak, since I, the

last, am old.” She also parcels out her difficult tale in small chunks, ten

chapters divided into six numbered sections each that the translators, in their

introduction, liken to cantos. Given the intensity of the story, one is

grateful for this manner of structuring that, akin to the Kaddish in Jewish

liturgy, provides an almost ritualistic and rhythmic quality for sustaining one’s

engagement with difficult subject matter.

The most striking feature of the novel, though, one which

only gradually reveals itself, is Bonanni’s unusual use of first person

narration. Her narrator, already in the first lines announcing his role, slips

in and out of the story. Sometimes he is present and referred to by the other

characters – chastised at times by the woman, for example, and explicitly

called by her “a witness here, our assiduous schoolteacher.” At other times he

appears so detached an observer that one questions his existance as a living

being, as he does himself: “But was I there? Maybe I wasn’t.” All we know for

sure is that he is described as a teacher who has accompanied the Fascists to

the monastery, “assigned to surveillance…alone and suspect” and “the only one

who had refused a weapon.” He also clearly operates as an explicit literary

invention of the author, serving as witness not simply to observe events but

also as a literary vehicle for the telling of the tale, in this latter role

functioning as a locus for the novel’s overarching theme concerning the

responsibility implicit in the act of witnessing. Through this alternating

presence and ineffability - and especially through the narrator’s behavior at a

critical moment - Bonanni brilliantly entwines the reader in her witness’

responsibility, forces the reader’s own moral self-examination. Not content

merely to tell a riveting war story, Bonanni never loses sight of her narrative

as an explicitly literary enterprise that calls attention to how a tale is told

and to the responsibilities involved in telling it. Adding additional

complexity to these themes, Bonanni alludes to a notebook La Rossa has kept to recount

her own story, a missing text with which the witness - and the reader - must reckon.

Bonanni, who published her first stories in 1927

and rose to fame due to winning a writing contest and to having been cheered

along by poet Eugenio Montale, did not live to see The Reprisal

published. Rejected when submitted for publication in 1985, the novel did not

appear in Italian until 2003, nearly 20 years later, and evidence exists that

Bonanni had worked on the manuscript since the end of the war – a span of some

forty years. 70 years later, readers of English can be grateful to have access

to a classic of World War II literature.

No comments:

Post a Comment