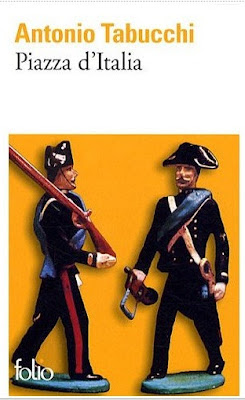

Antonio Tabucchi’s first

novel, Piazza d’Italia (1975), paints a family portrait spanning nearly one

hundred years of Italian history, from the country’s unification under

Garibaldi through its early birth pangs, expanding colonial empire, passage

through World War I, losses to emigration and influenza, Fascism, World War II,

and finally its post-war emergence as a democratic republic, a vast historical

panorama of a nation and family buffeted by the waves of great historical

events, rendered in sumptuous detail with a penetrating, granular examination

of every facet of Italian life, a sweeping depiction, extending nearly 200

pages, of-…

Okay, so I made up all

that stuff about granular examination and sumptuous detail. This is, after all,

Antonio Tabucchi, not some 19th century novelist who wouldn’t have

dreamed of compacting so much time into so few pages. But there’s something

winsome about Tabucchi’s restrained yet imaginative and engaging attempt to do

this, and, as his first novel, Piazza d’Italia also sows some grains for

what would emerge in his subsequent works. That Tabucchi choose to divide Piazza

d’Italia into three sections – the “restored” subtitle of the 1993 French re-issue

I read is “A Popular Tale in Three Times” - may suggest his own sense of the

unwieldiness of the narrative’s temporal compression.

Piazza d’Italia’s “Three Times” correspond roughly to three generations

of one libertarian, left-leaning family, whose surname is never provided as

though to emphasize their representational aspect. The first section tells of a

veteran of Garibaldi’s campaigns, the soldier Plinio (the names of many

characters in Piazza Italia echo through Italian history, and the

tradition of naming children after historical figures gets an amusing treatment

when a misprint on a poster results in several children being named “Imberto”

instead of “Umberto”). Plinio and his wife Esterina produce two sets of twins,

one identical (the brothers Quarto and Volturno) and one fraternal (brother

Garibaldo and sister Anita). Hints

of Tabucchi’s later manifestations of interest in the vagaries of identity are

evident here, since not only do the twins allude to Italy’s origins in the

Romulus and Remus myth and suggest continuity through time, but they also serve

as a concatenation of identities within the family. Adding to this concentrate are

multiple iterations of the name Garibaldo, including when the town hall denies

Plinio his initial wish to name each of the identical twins Garibaldo, or a

generation later when their brother Garibaldo’s son, yet another Volturno,

discards his own name and adopts that of his father (there’s an indispensible

family tree provided in an appendix). Moving gingerly from one generation to

the next, Piazza d’Italia traverses Italian history, its events filtered

through the Tuscan village of Borgo and marked in the town piazza by the serial

replacement of the statue at its center to reflect whichever political figure

is most popular at the time. The town’s first cinema also comes to play a

starring role in marking later historical events, its ostensible function loaned

out for speeches, rallies, and other gatherings having nothing to do with

cinema, causing the poor population to wait repeatedly in vain for Giovanni

Pastrone’s epic nationalist film Cabiria to finally reach the town. While

the family’s men go off to fight or emigrate to the Americas or stay to combat

fascism or drift into the deserts of Africa, its fierce and smart women form

the moral center of Piazza d’Italia and play as active a political role,

albeit often behind the scenes, as their fathers, husbands, brothers and sons. Some

of the references to Italian particulars may be lost on non-Italian readers (just

as Pereira Maintains, despite its setting in Salazar’s Portugal, was read

by many in Italy as a warning of resurgent fascism under Berlusconi), but at

least for historical background, endnotes help fill gaps in the reader’s

knowledge.

It is funny that as I was reading your commentary I was thinking "One Hundred Years of Solitude", before you referenced it.

ReplyDeleteI think that it is often very interesting to read a writers early works. As you found here, one often finds the embryo of ideas and con concepts, often less developed.

I must read more of Tabucchi and I must read Pessoa!

Thanks, Brian. As I noted in my comment to your Tabucchi post, you can read him without Pessoa, but reading Pessoa definitely helps unlock of good deal of what's going on.

DeleteThanks for the review. I was unawares of this Tabucchi novel. Your description makes me think of another novel I have yet to read: Elsa Morante's History: A Novel.

ReplyDeleteMorante's novel is high on my list too.

DeleteI read about 25 pages of this in Italian before accepting the fact that my sorry ass Italian was too inadequate to try rushing through this in one week. Am reading and enjoying a translation of a different Tabucchi now, but I was partic. glad to read this post of yours since the multiple names thing was a little too much for my, ahem, s_____ a__ Italian to cope with and comprehend all that well. Mille grazie for clearing all that up!

ReplyDeleteI'm glad to hear you say that, Richard, as keeping track of the multiple, multiplying Garibaldi while reading this in French was a challenge! But once I settled on the notion that they were all just manifestations of some eternally recurring Garibaldo, I figured it wasn't so terribly important to keep them distinct - or least that I'd probably be forgiven if I wasn't able to do it myself.

DeleteThis sounds like a really different Tabucchi. What would have been a great achievement for any other novelist after a fruitful career is only the starting point here.

ReplyDeleteMorante's history was part of last years Literature and War readalong and that was definitely Marquez like. A wonderful novel.

It will be intersting to read Tabucchi's condensed attempt at historical writing.

And thanks so much for joining btw and I'm glad you chose this book. We have now a really nice collection of reviews.

ReplyDeleteCaroline - thanks for making it all happen! You articulated just what I felt about Piazza Italia - that for some writers it would have been a high achievement, but that for Tabucchi it was just a launching point.

DeleteThanks for the review - just read Pereira Maintains and really liked it, so I'm sure I'll get to his first book one day. I'll probably read more of the later ones first, though - I like going back to a writer's first novel with the knowledge of what came later, to see where it all started.

ReplyDeleteThanks, Andrew. I agree - it's interesting to travel backwards through a writer's work to his or her origins. And yes, I'd endorse your reading some of the later ones first. To me, they're more complex and interesting. I do hope, however, that Piazza Italia will eventually be available in an English translation, as it's certainly worth reading.

Delete